Ukrainian Jews Celebrate Passover Amid Crisis

Jews around the world are celebrating the beginning of Passover tonight. The holiday commemorates the exodus from slavery into freedom. For Jews in Ukraine, the holiday has an especially powerful meaning this year, coming on the heels of a secular revolution. NPR’s Ari Shapiro reports for Here & Now from Donetsk.

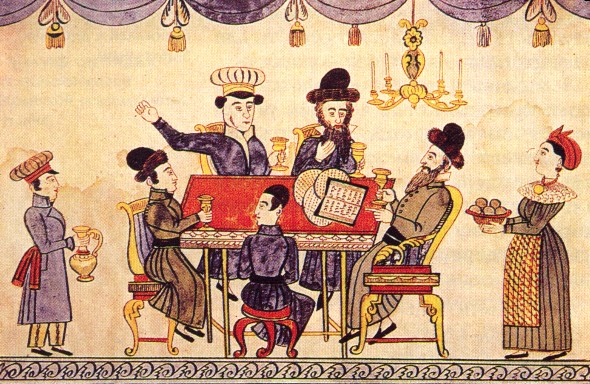

At every Passover table tonight, the youngest child will sing this song. Children at a synagogue in Kiev are learning the words to “Mah Nishtana.” They ask in Hebrew: What makes this night different from all other nights?

Adults in Ukraine can ask a similar question this year: What makes this Passover different from all others? It’s a question Rabbi Alexander Duchovny has been thinking about a lot. He uses a Hebrew phrase to describe it.

“Passover is z’man heiruteinu. Time of our liberty. Time of freedom. And especially for Ukrainian Jewry, and for Ukrainians. This is time of liberty,” he says.

Duchovny is a progressive rabbi, and like many Jews in Kiev, he joined thousands of protesters in Independence Square this winter, demanding a change in government.

In the Passover story, Moses demands that Pharaoh “Let my people go.” And Duchovny sees a thread connecting ancient Egypt to modern-day Ukraine.

“We started our liberation 3,000 years ago, and we still are in the process,” he says.

The last century of this struggle has been especially difficult for Ukrainian Jews. Massacres. Pogroms. And of course, the Holocaust.

Rabbi Duchovny says he is only alive today because a Ukrainian family sheltered his mother during the war.

“My mother was a teenager when she was taken to be killed. On the way to be killed, she ran away together with her younger sister and a Ukrainian family saved my mother.”

Ukrainian Nazi collaborators killed his grandparents, his aunts, and his uncles. But he chooses to focus on the other side of the coin: The Ukrainians who kept his mother alive.

Decades after the Holocaust, during the Soviet era, people whose passport said “Jewish” were not allowed to attend the University of Kiev. Leonid Fineberg had that experience.

Today, Fineberg runs the Jewish studies department at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, the university that once refused to admit Jews.

“The rate of anti-Semitism in Soviet times was extremely high. But it wasn’t just Jewish people. Ukrainian dissidents couldn’t find jobs either. Everybody had these problems,” Fineberg says.

Across town, there’s a Hasidic synagogue, where Orthodox Jews have been worshipping, sometimes in secret, for more than 100 years.

Israel Radutsky is the groundskeeper here. He remembers when he was a child how cautious people had to be when they celebrated this holiday.

“People could come here at Passover and get some matzah,” he says. “But they had to hide it inside of a pillowcase so nobody knew they were carrying it.”

So now, the people of Ukraine have overthrown the government they saw as oppressive and corrupt. But the story is still unfolding.

Protesters and government forces are shooting at each other in the East. Russia has annexed Crimea. Rabbi Duchovny says this underscores a central lesson of the Jewish experience.

“ Liberation never ends. Liberation starts. And it goes and goes and goes. And this is what Jewish people learned during the centuries.”

I asked each person I interviewed: Where in the Passover story are Ukraine’s Jews right now? Are you enslaved in Egypt, still living under the Pharaoh? Are you wandering in the desert for 40 years?

Everybody gave a different answer. But not one person said they had reached the promised land.

2020 Nike Air Jordan 1 Mid GS "Pink Quartz" 555112-603

.png)